Defining Community

“Defining community is like trying to define life,” said Ranga from Beyond Social Services. That’s because community can be an abstract concept, even though it’s expressed in tangible, physical ways. It’s woven into the fibre of humanity, and it’s difficult to identify the threads that comprise it.

Still, let’s try.

Let’s start with the Cambridge dictionary: Community means “the people living in one particular area or people who are considered as a unit because of their common interests, social group, or nationality”.

From this definition, we understand that a community is made up of people who share something in common. And it doesn’t matter if these members were previously disconnected, because now they identify with others with whom they share a set of commonalities.

This could be a common interest—even funny dog videos compel people to form loose groups online.

A common enemy could also bring individuals together to form a community. It could start with something as small-scale as the noises in street soccer courts outside your HDB to larger-scale issues like nature preservation or battling a pandemic.

But it’s not just about a bunch of people coming together, says Shi Hui of Khoo Teck Puat Hospital’s Population Health & Community Transformation team. “If there’s no sense of camaraderie, then it’s not a community.”

The definition of a sense of community introduces another dimension to the community experience: “a feeling that members have of belonging, a feeling that members matter to one another and to the group, and a shared faith that members’ needs will be met through their commitment to be together.” That comes from an article published in the Journal of Community Psychology in 1986.

More than 30 years later, that definition still resonates.

Belonging to a community is a way to identify with something beyond ourselves. As Hana from the Singapore University of Social Sciences put it: “It’s a basic human need to desire to belong and be part of something.”

Belonging, in fact, is central to the concept of community. Belonging is best created when we join with other people in implementing initiatives that make a place better, writes Peter Block in The Structure of Belonging. Block is an author and consultant in the areas of community building, civic engagement, and organisation development.

“To belong” means to be related to and be a part of something. But the word has another meaning, one that connotes ownership: something belongs to me. So in the context of community, belonging means acting as a creator and co-owner of a community.

Communities feed a social need—the basic human desire to belong. They can also fulfil other needs, of course, like help you build a professional network, find advocates for a cause, or simply escape boredom on Saturday afternoons.

For NVPC’s Joel, being part of a community makes him humble. “I need someone to tell me I’m an idiot sometimes. I need people to tell me I’m wrong. I’m the product of my communities.”

Communities exist on different scales

Region

A regional community could be the district you belong to. It could also be an ethnic enclave that you identify with.

In these districts or ethnic areas, people grapple with larger-scale issues and interests that bring them together. Your district might want to preserve heritage or nature-rich areas that are affected by urbanisation plans. Your racial community might want to promote a greater understanding of your culture among Singaporeans.

Each of these has an effect on one another’s existence. You and your neighbours chose to live there for a reason, and your actions affect one another.

The sundry shop exists to sell goods to residents. Students from the school need the library. The hawker centre, as well as the cafes and food shops, may even reflect the community’s history and diversity in the dishes they sell.

You acknowledge that you belong to this community when you participate in its daily life and get to know the people who live and work there. When you boast to your friends that the humble hole in the wall a few blocks down is the birthplace of a famous dish, you’re acknowledging a narrative that’s shared by the neighbourhood. When you and your neighbours complain about the destruction of a shophouse, you’re acting as a group of people with a common cause.

Neighbourhood

Take a walk (for real or in your mind) around your neighbourhood. Consider the places around you, how they’re interconnected, and in what way they’ve touched your life.

They might include:

- A hawker centre, and all the vendors within bakeries and cafes

- A sundry shop

- Service businesses, such as for repairs

- Retail stores and pharmacies

- Clinics

- A school

- Your neighbours

- The library

Block

Floor

Community: intentional or organic?

When thinking about communities, it’s important to understand that they may either be intentional or organic.

For example, you might intentionally build a community of environmental activists or volunteers to help the elderly. You might form a book club or a chat group of startup founders.

At other times, activities might come first before a community is formed. Maybe the same group of moms take their toddlers to the park on Saturday mornings and end up getting to know each other. They discover that they have the same interests or struggles and plan activities to address them.

People with the same desires or problems join these moms, and as they continue to meet, befriend each other, and help out one another, their group becomes a community.

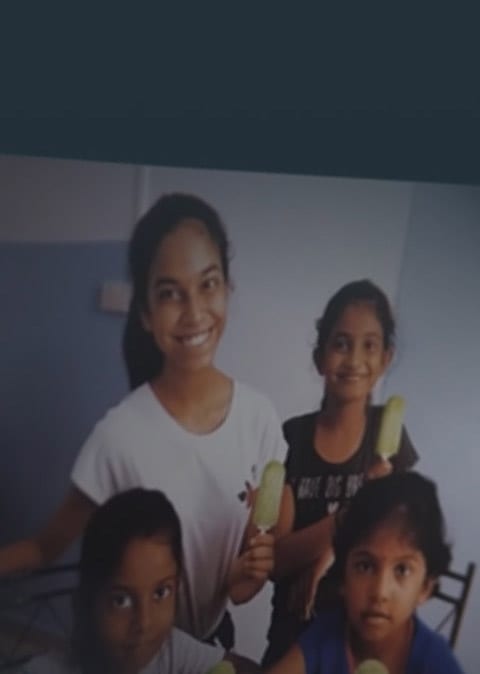

Elysa of Campus Impact had a similar experience. “It formed because one of my kids dropped out of school. And he brought a friend, and that friend brought another friend,” she shared.

They started teaching programming modules and eventually included informal lessons relating to life and relationship skills. The kids enjoyed it and brought more friends.

“We realised they had additional needs we could meet through the centre. We opened a room for them, gave them WiFi and a couch, and they started to come by themselves [even with] no one to engage them. I felt bad for the longest time but it was through that that even more kids came in,” said Elysa.

The relationships formed in the group, supported by the physical space, kept them coming back.

Next Chapter: The Community Canvas Framework