Can you really change a community’s culture?

One fact about culture is that it’s dynamic, not static. That means it can and does change.

Of course, introducing change is easier said than done. When values and behaviours become normalised and internalised, “they can become difficult to change or understand if there is no room to question the existing practices,” says James from Undelusional.

Michelle adds that a desire to be polite might hold people back from questioning aspects of culture. A few developers also pointed to Singaporean culture as a barrier to change: “Even if [something] doesn’t make sense, the Singapore culture is to not question,” says Michelle.

The problematic concept of an “ideal” culture and who should define culture

Community founders usually define a community’s culture by tying it to their vision for the community. After all, it’s inevitable that when someone has a vision for a community—especially when they’re the founders—they’d have a good idea of how they want the culture to be like, too.

For example, in its website, Mutual Works is described as a “home for entrepreneurs & freelancers to work, play, learn & grow together”. This statement alone reveals the vision for the community, and also indicates what its ideal culture would be: one characterised by collaboration, fun, and shared learning. This would differ from other co-working communities who have their own visions and ideal cultures.

In general, though, developers agreed that an ideal community culture would be a balance between giving and receiving.

The first step to achieving this balance would be to make sure that you’ve correctly identified members’ needs. But even this step is problematic. For one, if your community is large, how possible would it be to identify every single member’s needs?

Some developers believe that a community can define its ideal culture through general consensus as well—an idea that resonates with ABCD practitioners. ABCD practitioners don’t believe that communities should exist to identify and serve members’ needs. Instead, they view members as assets to the community.

In ABCD’s bottom-up approach, the “ideal” culture must be defined by the community. Whatever this ideal culture may be, it would involve members discovering their potential and utilising their assets, collaborating with each other, and taking ownership of the community.

Is the “ideal” culture achievable?

While developers may set the norms, rituals, practices, spaces, and other symbols to reinforce their “ideal” culture, they also need a core group to help spread this culture across the community.

“In the beginning of the group, you need to define the norm… It’s the core group that will spread it out further, so if you do not have that core group, it is difficult,” shares Atiqa of Repair Kopitiam.

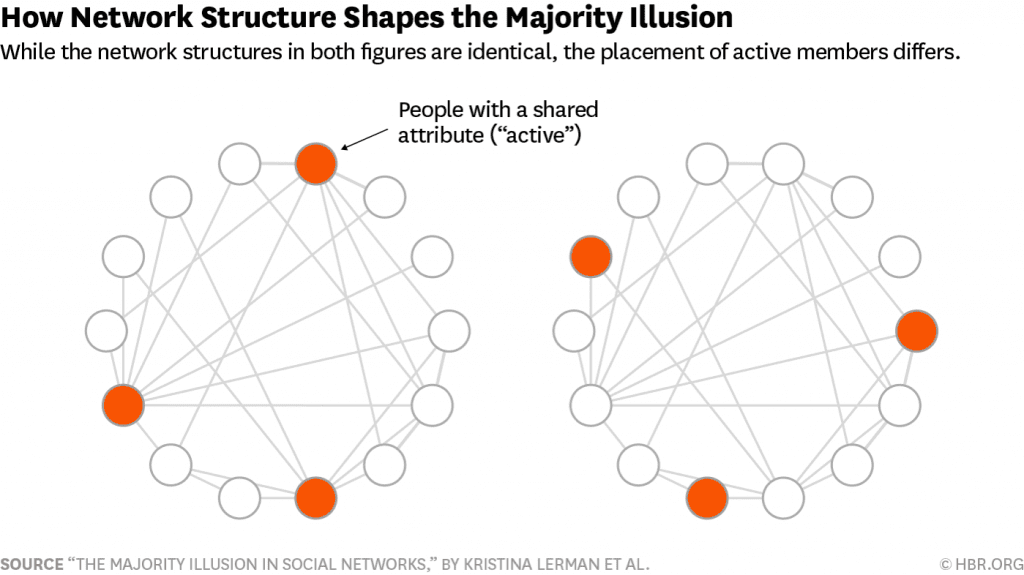

Beyond the core group, developers must also pay attention to influential people in the community who can either help to share and reinforce this “ideal” culture or derail the leaders’ efforts. According to researchers at the University of Southern California, people who are both widely and strategically connected can make ideas, behaviours, or attributes appear more popular than they are. And when people deem these things popular, they tend to adopt them, too.

The key component: trust

To reinforce or transform culture, it’s crucial to have trust between and among members and leaders. As a leader, you can help build trust and psychological safety by instilling confidence and affirmation among members.

Most importantly, you need to provide the space to fail.

For example, Vincent shared about the first time he let the members of A Good Space organise their year-end party without his involvement. At one point, he struggled to keep himself from intervening when there were too many ideas. He faced the dilemma of whether to step in or to let the event fail and allow the community to learn from the experience.

Another aspect of trust is having psychological safety to be able to question things, such as community norms and practices. Without questioning such things, communities would fall into the illusion that their culture is static, and would fail to perceive areas where they can improve.

One developer adds that creating trust requires a lot of face time. However, there are also online communities that thrive. And some situations—think, for example, Singapore’s circuit breaker during the Covid-19 outbreak—force communities to swap physical meet-ups for virtual events. Video chats would then be the closest they can get to face-to-face interaction.

Previous Chapter: Cultural Tensions in Communities