In this case study, we visit the lived experiences of 5 Groundup Founders who found a compelling motivation to serve others.

We explore the stories of 5 individuals from diverse backgrounds – from a mother grappling with the loss of her child to suicide, a youth who faced bullying and mental health struggles, an academically disadvantaged student, an ex-offender, to a youth who grew up in a financially challenged family, these 5 individuals share how personal struggles motivated them and shaped their journey towards helping others in similar circumstances.

The Triggers That Began a Journey

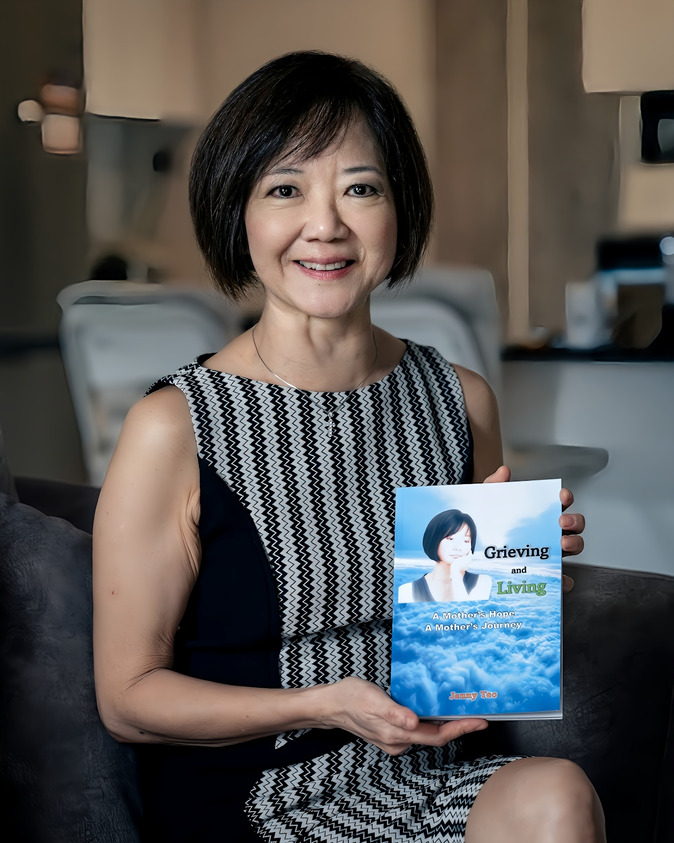

Jenny

The first time Jenny dealt with suicide was through text. Her son’s friend had informed her of her son’s intent to end his life. Distressed and panicked, she was inclined to reach out and ask for help – but there was no one. Feeling scared and “at a loss as to what to do,” no one, not even herself, knew how to help her son, Josh. He eventually succumbed to suicide.

For months, Jenny grappled with grief. Even as she repeatedly listened to the audio tape recording that Josh left behind, she struggled to come to terms that her son was gone. The pain of losing her only child, alongside the stigma intricately tied to suicide, felt suffocating as she was mostly left to suffer in silence.

The loss struck her deeply, as she recalls, “There was really no one I could call who knew anything about the suicidal mind or had a similar experience to advice or share with me.”

Having experienced a time where little to no support was made available to her, she recognised how important it is for struggling caregivers with suicidal loved ones to have someone they can talk to or to seek advice from. Something more had to be done, but who will do it?

Taking the matter into her own hands, she founded Stigma2Strength (Singapore), a groundup aimed at public pyschoeducation and seeks to support suicide loss survivors and parents with suicidal loved ones. Additionally, she is also the co-founder of PleaseStay Movement, an advocacy group rallying for suicide prevention.

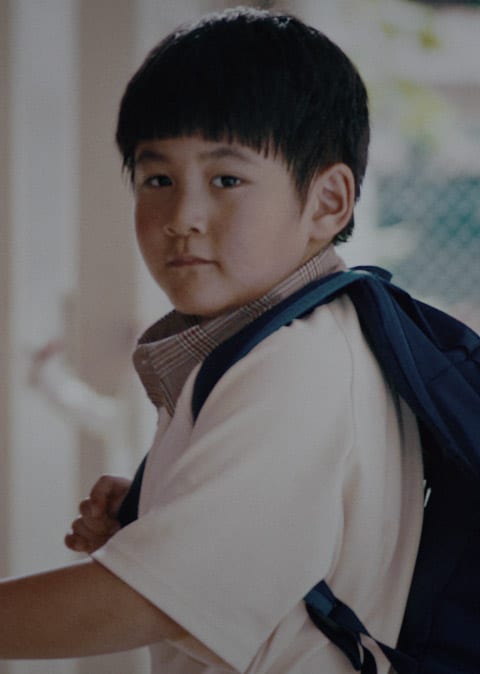

Ryan

Bullied in his secondary school days, Ryan was incessantly taunted by his peers with crude insults about his looks and the way he talked. When he tried to reach out for help, he learnt the debilitating effects of being stigmatised for his mental health the hard way.

His pleas for help were constantly ignored, minimised, and met with apathetic dismissal. In his words, “Imagine having your voice stripped away from you unwillingly. Imagine having people telling you that mental health conditions do not exist, and it’s all in your head. Imagine having a panic attack but your teachers decide to label you as rebellious and attention-seeking.”

It left Ryan trapped, isolated and alone in a dark unimagined abyss of anguish that no one bothered to understand. The culmination of the bullying coupled with the blatant disregard that followed when he reached out for help drove him to attempt suicide multiple times.

Instead of having access to the help he so desperately needed, he was forced to leave school. With no other forms of support, he slowly became isolated and was left to fend for himself in dysfunctional circumstances.

Little pockets of compassion from peers and teachers during his polytechnic days helped him to overcome his experiences with bullying, depression, and social anxiety. Additionally, it led him to realise that anyone has the potential to evoke change.

With his lived experience, he became a mental health advocate but aspired to do more – ‘I wished that narratives like mine could spark hope for others who may be struggling with their mental health.’ As a result, The Catalyst Collective was formed.

David

Being from the Normal Technical (NT) stream, David recalls how “most of us weren’t strong academically and had little motivation to do well academically.” He was aware of the merit and limitation of support extended to students like him.

It is often the absence of motivation – not necessarily tuition – that holds the students back.

He felt lucky that the accidental discovery of a love for teaching greatly motivated him to double up on his efforts and study harder.

As someone with a personal philosophy to help whenever he could, he had always had the desire to better support students from disadvantaged backgrounds. This led to the establishment of I Am Talented (IAT), a groundup aimed at helping disadvantaged youths explore and find passion in other non-academic pathways.

He believes that by giving students a reason to pursue their areas of interests, they would be able to better strive in their academics.

Andrew

When he started his journey of reintegration and rebuilding a new life 22 years ago, Andrew found that what made his journey successful was the fact that he was able to become part of a community. A strong support network of friends and cycling mentors helped to keep him accountable.

Having had various mentors within the church community for 8 years, that experience taught Andrew “the importance of being part of community, as well as having a mentor.”

Understanding the importance of having someone extend a helping hand and guidance, and being aware of the issues of recidivism, he set his sights on using his past experiences to help fellow ex-offenders. Hence, he founded Break The Cycle, a groundup that utilises cycling and community as a platform for ex-offenders to connect and better reintegrate back into society.

Zulayqha

When Singapore went into its Circuit Breaker, Zulayqha saw first-hand the devastating impacts of COVID-19, especially on low-income families – children sitting at the corridors outside of their homes, hunched over their laptops to share their neighbours’ Wi-Fi and neighbours re-washing disposable diapers to save money due to their inability to secure stable employment and income.

Witnessing a large community in desperate need of help triggered her memories of similarly precarious times when she needed help. Having received help from the wider community to tide over difficult times, she felt that it would be ignorant of her to look the other way, especially when so many families were struggling.

Motivated to do something, she explains, “The help that I have received to support my family needs has definitely been a push factor for me to pay it forward to those who face the same or similar struggles as me.” As a result, she started The Project Hills, a groundup that helps to distribute daily necessities to low-income families living in rental communities.

If the hope is for us to be an inclusive society with a strong social fabric, we have to look out for vulnerable individuals of all communities across all demographics. The question often posed is: how can we better support people in times of need?

Intuitively we might turn to the government, charities, or social work professionals for answers. However, it is worthwhile to take a step back to consider if they are the only solutions available.

Perhaps, we, as seemingly ordinary citizens, have unique perspectives and assets that formal institutions may not be able to offer, and can be the ones to step up to build stronger communities and forge more tightly woven safety nets to ensure that everyone is able to access the help they need. Why should we care? Because it could have been us – any one of us – who happens to need a helping hand.

How Strength Arose from Lived Experiences

After losing her son to suicide, Jenny attended an event at Caregivers Alliance, which provided a safe space to share her story of loss. Subsequently, she was invited to speak in front of a live audience at an event by Caregivers Alliance, which provided a closure that greatly aided in her journey of healing and recovery.

Even whilst she was still in a vulnerable position, she sensed the power of sharing her story and starting more of such conversations to break the stigma surrounding suicide, and to provide support to struggling suicide loss survivors and caregivers like herself.

She explains, “As suicide is highly stigmatised in Asian society, a ‘lived experience’ is usually effective in helping break the ice when it comes to broaching the subject of suicide and suicide loss. It is through talking and sharing without the fear of being judged that solutions can be found and suicides can be prevented.”

They say that every cloud has a silver lining, and in the stories of founders of groundups like Jenny, we see that they found strength in their lived experience of having gone through such distressing times.

For Ryan, when he entered polytechnic, he found hope and strength in little pockets of support from people who believed in him. This gave him the courage to forge on and granted him the foresight to realise that his past negative experiences do not have to define him.

On the flipside, Ryan found that the sharing of his lived experience can truly be an exceptionally powerful tool one can harness to help.

Stories provide a beacon of hope and a sense of connection for those in despair. They help put forth the message to struggling individuals that help and support are always available, that dysfunctional times will pass, and that they will be able to emerge out of their crisis, stronger and more resilient. Even within his team in his groundup, The Catalyst Collective, some members have come forth in sharing their own experiences with their mental health struggles.

Ryan shares how even though most of us may not be experts or psychologists, “our experiences allow us to better empathise with fellow youths who may also be struggling and provide them the peer support (and community) that they need.”

Herein lies the strength of lived experiences, in that we do not have to be a certified therapist or someone extraordinary to be empathetic and compassionate. Sometimes, simply being there and listening, providing a safe space for people to be open and vulnerable, is a monumental act.

Whilst Andrew never shied away from sharing his story of being an ex-offender, it was not until he started his groundup, Break the Cycle, that he became more open about his identity as an ex-offender. He found that often, there is a stronger sense of personal connectivity when he was more open in sharing about his experiences.

Through his experiences of volunteering and working with various organisations within the social sector, he found that often, the first step of helping may just be being able to truly acknowledge the reality and challenges that these individuals face, to be able to hear, respect and understand and empathise with them.

Recognising a transformation opportunity, he adds, “I saw a need for fellow ex-offenders not to be ashamed of their past, but to embrace their past as part of who they uniquely are which can be used for a greater purpose.”

Whilst volunteers and the public might be eager to help, it might be difficult for individuals without lived experience to know what the right words are or what sort of actions to take.

However, sharing stories and accounts of past experiences provide a raw sense of real empathy that can help ensure that more people are comfortable in reaching out for help when they are in crisis.

Shedding more into how ex-offenders perceive this, he explains how “intimidated they are in interacting with others that do not share similar life experiences to them,” stemming from feeling unworthy or inferior due to their past or social standing.

Through civic participation, we see how people like Jenny, Ryan, David and Andrew can bridge the “last-mile” service delivery gap to ensure that vulnerable individuals in our community are better supported.

Like Andrew, alongside her own lived experiences and first-hand interactions with families in her neighbourhood, Zulayqha also saw the need to bridge a ‘helping hand’ delivery gap. Taking into account how it may be difficult for the large-scale, top-down rationed support to accommodate different needs, this helps to ensure that not only support is available, but they also suit families’ with various needs. After all, the effectiveness of support lies in whether it can address the real – not assumed – needs, and lived experiences shed light on what they could be.

David, who through his own experiences of being a Normal Technical (NT) student, found that often, poor academic performances of youths are misconstrued, with motivation towards studying a key factor.

For him, it is a good thing that the community at large tends to offer academic support programmes, but it doesn’t quite tackle the root issue. At the end of the day, he adds, “it is a function of motivation and also structure.” Hence, some of the help provided externally, while good, might not address the root issue.

Reflecting on how working towards a goal of becoming an educator greatly aided him to strive harder in his academics, he realised that the underlying issue might not simply be a lack of academic support, but a lack of having an aspiration to work towards.

He explains, “The issue isn’t asking a child to study harder, rather it is about seeding the ‘why’. Once they can articulate the ‘why’, they will find it much easier to run.”

Despite once finding themselves at rock bottom, Jenny, Ryan, Andrew, Zulayqha and David found that lived experience offered them a perspective from the ground up.

Having gone through adverse situations allows them to have more intimate insights on the needs of vulnerable individuals, which then puts them in a unique position to better craft solutions – a “groundup” solution.

Exploring a Solution From the Ground Up

What does a “groundup” solution look like? For one thing, it can mean knowing where service gaps are and curating initiatives to bridge them. To provide effective services and solutions, charities and governments turn to various sources for advice. Some look for experts and research, others use hackathons to generate innovative ideas. These are all very much important and useful. However, we have yet to place a greater value on the voices of those whose opinions matter the most – the service users themselves (Threlfall & Buchanan, 2013). A solution from the ground up lends us that valuable perspective.

Reflecting on her own experience, Jenny discovered that learning and telling the truth, while “keeping the narratives as authentic as possible and confronting the blame and shame in the most honest way as possible,” triggered a relatable response from the public for them to open up about their vulnerabilities, whether as someone contemplating suicide, a suicide survivor, or a suicide loss survivor.

Conversations about suicide and loss are important in providing support and increasing awareness of suicide, but Jenny realised that such measures were still not substantial enough to prevent suicide. What was still missing was public education on suicide, where it is “very lacking in our society due to the deep-rooted stigma revolving around suicide.”

When she lost her son, she did not understand the reasons behind what drove him to suicide. As she processed her grief, she read books relating to mental health, depression, suicide, and watched countless YouTube videos of suicide loss survivors. With more structured knowledge, she could better understand the deep psychological turmoil that her deceased son Josh was in – a state he could only articulate as “unbearable pain” in suicide notes he left behind. This led her to recognise the importance of public psychoeducation on top of advocacy and awareness.

Realising “all it takes is an act of compassion”, Ryan founded The Catalyst Collective, a groundup aiming to share personal narratives of adversity to cultivate more empathy within youths to build a healthier landscape for mental health.

He adds, “Our belief is that support is a two-way thing. When I am struggling, you are there to help me; when you are struggling, I am there to help you. After all, you do not have to be someone special to be a good friend.”

It does not take “someone special”, but it does take a keen eye and special attention to know what exactly is needed. Bouncing ideas off with her family and friends, Zulayqha shaped the establishment of The Project Hills, where their unique value was in the ability to connect more intimately with the individuals they serve. Zulayqha and her team conduct door-to-door surveys to better understand the needs of the community, customising welfare packs for each family to better meet their needs.

Groundup solutions can also take on a different form, whereby founders, through their journey of self-healing and recovery, figured out novel ways to cope with their situations, which they then incorporate into their group’s initiatives and projects.

Andrew states, “As an ex-offender myself, I experienced the challenges (both internal and external) of reintegrating and rebuilding a new life. At the same time, I also learnt what are the key ingredients that contribute to a successful reintegration and rebuilding of a new life.”

On his journey to reintegration, Andrew found new, healthier ways to cope. Cycling was introduced to him, and it was a hobby he grew to love. What started as a way to keep healthy became a new form of social support. Cycling mentors encourage him, give advice, and most importantly, help to keep him in check.

Along the way, he became friends with an ex-offender who was also an avid fan of cycling. He explains, “Break the Cycle didn’t start until I tested it out when I met the first ex-offender cyclist by chance. We helped him not only with his bike fit and other aspects of his cycling proficiency but also the social participation with other cyclists.”

This accidental interaction was an epiphany for him –building a new avenue of social support. To help lessen the risks of re-offending, cycling could be used to connect and help an ex-offender to reintegrate by using the sport and cycling community.

Like Andrew, the perspective David gained from his own experiences helped him recognise the gaps in existing student support programmes, which then allowed him to come up with a solution that is more tailored to the needs of students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

In summary, the word “groundup” refers to three “M”s –mindset, methodology and mode of dealing with problems.

Mindset being resourceful and proactive in taking action, methodology as adopting a bottom-up approach to issues, and mode being a group coming together voluntarily for a self organised project or initiative, such as Stigma2Strength (Singapore), The Catalyst Collective, The Project Hills, Break The Cycle and I Am Talented.

During COVID-19, we saw a spike in the number of groundups founded in Singapore. Of course, one does not have to experience the issues first-hand to do something about it – anyone with the groundup mindset and adopts a groundup methodology can establish their own groundup.

But for those with a lived experience, introspection together with a caring and willing heart, allowed them to be more conscientious and targeted, always keeping the needs of those they serve at the forefront.

Turning Personal Setbacks to Collective Strength

Taking concrete steps to contribute to the community often requires grit, determination, proactive learning, a supportive network, and a little luck (amongst many other factors). Even then, not all potential or current founders may have the luxury to establish or sustain their groundups, due to a wide array of problems that almost all groundups would inevitably run into at some point. These include a lack of systematic knowledge, funding, credibility, manpower, and more (NVPC, 2023).

Lived experience and a fiery passion are important, but as Jenny states, passion is merely the “key in our hand to sit in the driver’s seat”.

She soon learned that “being merely a suicide loss survivor and not a mental health clinician was a major setback,” especially when one endeavours to create public awareness on youth suicide prevention.

Learning more about the myths and fallacies of suicide through self-education was an important step for Jenny when starting Stigma2Strength(Singapore), so that she could better garner traction in building understanding of suicide in Singapore.

Building a knowledge base is important, but so are other innate factors like grit, perseverance, and intrinsic motivation.

Although Ryan had the idea and the desire to start his groundup back in 2020, he faced many challenges that proved to be tricky when trying to establish it, noting how it “wasn’t backed by any school or organisation in the beginning and took quite a while and effort to search for the right people to work with.”

Despite multiple failed attempts at finding the right people to work with and unsuccessful launches of his events, he remained steadfast. His efforts paid off when he rallied the right supporters in his change-making journey. Recruiting close friends and pitching ideas to relevant organisations like the National Volunteer & Philanthropy Centre (NVPC) and National Youth Council (NYC), he successfully launched his first physical prototype event, #ReWritingNarratives in 2022.

As Ryan mentions, groundups often lack credibility and legitimacy which makes it difficult for them to garner enough support for their initiatives. Zulayqha is all too familiar with such issues, as when she first started, Project Hills often faced dismissal and questions about their targeted causes and initiatives, having to distinguish themselves from other groundups.

The Project Hills team tackled this challenge by coming up with more marketing collateral from the lens of the wider community. Including “engaging our social media audience on a weekly basis and updating our social media stories to psycho-ed the enquirers.”

Ryan and Zulayqha are not alone in their struggles with credibility. In the beginning, David was also hesitant about starting on his own, as he understood he lacked the credibility to ensure his initiatives would be successful.

So, he started by first volunteering at the United Nations Association of Singapore (UNAS). From there, he was able to put out his ideas and connect with like-minded individuals. Running pilot programs with the newfound support, especially at such a prestigious organisation, gave him the much-needed credibility to boost the establishment of I Am Talented (IAT).

Aside from the deliberate efforts to build credibility, David’s philosophy of helping whenever he can serve as an anchor for his sustained action.

At the height of COVID-19, he found himself in another position to help. This time, instead of youths, he was concerned over the lack of financial support for large low-income families awaiting financial aid.

With IAT, there was uncertainty in starting, but this time, he was more experienced. Building on the credibility he established from IAT, he reached out on social media to garner support from people who felt the same way. Moreover, he was well-connected to organisations like the NYC.

From there, Project Stable Staples (PSS) was founded. Appealing to the generosity of the public and the publicity garnered by NYC, PSS was able to raise more than $150,000 to help low-income families in rental communities’ tide over a difficult period, a time where many faced economic uncertainties due to retrenchment caused by the pandemic.

As we see, the groundup journey is hardly smooth sailing. While some groundups face the issue of a lack of manpower, Andrew recalls that there were many volunteers eager to join his cause. The more the better, right? Not quite.

He recalls, “Some cyclists brought in bad cycling habits that compromised the safety of our regular cyclists and some couldn’t put the community interest above theirs and regarded our groundup as merely a cycling group.”

When people joined without considering the social mission of Break the Cycle, it compromised their mission to create a safe space for the community. Andrew learnt the hard way that sometimes the quality of volunteers mattered more than the numbers. Hence, he tightened entry requirements and ensured that volunteers looking to join are thoroughly screened before they are invited on cycling rides.

As he persevered and overcame the challenges, he continued to build rapport with even more organisations like Singapore Prison Service and Yellow Ribbon Singapore.

A part of his ability to connect with such large stakeholders can be attributed to him building upon his existing network from his years of working within the social sector. Rapport with established organisations brings a huge advantage as it allowed him to fund bigger and better projects like their year-end endurance rides.

A lot of work goes into establishing, growing, and sustaining a groundup, and oftentimes, simply banking on personal insights and passion is not enough for a successful launch.

However, it remains that the work groundups do is a spark that has great potential to kindle hope for someone in need. The lived experiences of groundup founders like Jenny, Ryan, Zulayqha, David, and Andrew may be in the minority, but they are incredibly powerful and precious.

They demonstrate that we should disregard binary labels when talking about who the givers and receivers are because everyone can give.

Bibliography

- Hong, D. (2017). Exploring informal social & cultural activism in Singapore: A study on local ground-up initiatives.

- Shafik, M. (2021). What we owe each other: a new social contract for a better society. Princeton University Press.

- Threlfall, V., Twersky, F., & Buchanan, P. (2013). Listening to Those Who Matter Most, the Beneficiaries. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 11(2), 41–45. https://doi.org/10.48558/8BWV-8A71