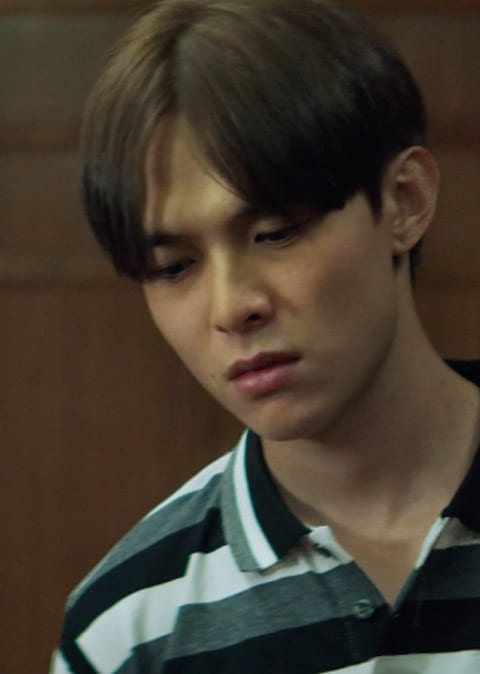

He was locked up five times before he was 25. But Mr Firdaus Abdul Hamid changed his life after a road accident almost killed his family. Now, he works with ex-offenders and youths to help them get back on track.

Firdaus Abdul Hamid sat in the detention barracks (DB) located in Lorong Kebasi, next to the Kranji Camp, for the fourth time in three years, talking to no one.

He was 23. “I had anger issues and about three months before my release, I was tested psychologically and I failed. Then I was clamped and sent to the ‘hole’,” he recalls.

“I started talking to my hands, to the light coming in from outside. I thought I was going cuckoo and decided enough is enough, I had to do something so not to masuk lagi (Malay slang for jailed again).”

Turning 40 this year, Mr Firdaus is co-founder and executive director of non-profit organisation Human Hearts, his troubled past in his rearview mirror as he seeks to empower inmates, ex-convicts, families of incarcerated individuals and at-risk youths.

He and his team — many themselves ex-offenders — help them regain their confidence and find their footing in life. Mr Firdaus’ own life has been a series of upheavals; in his youth, admittedly self-engineered, then later in life, horrific blows of fate.

Above: Members of the cofounding team of Human Hearts are all reformers. From left to right: Mohd Fadhil Husin, Muhammad Andyn Abul Kadir, Firdaus Abdul Hamid, Mohamad Shaifudin MD Yusof, Taufiq Yusof and MD Ali Jinnah.

The Beginning of a Cycle

By 9, Mr Firdaus was a bully who smoked, stole and played truant. By 13, he joined a gang, and was once so badly beaten up his classmates dubbed him “the Hunchback of Notre Dame”. At 15, he dropped out of school.

He got a job as a dishwasher at Changi Airport, then progressed to 12 to 16 hours as a canteen helper, a cleaner, a busboy, earning an average of $1,000 and $2,000 a month. His mum got an occasional $50 or $100 for expenses. The rest, he frittered away “going to clubs and getting up to other mischief”, resulting in minor traffic offences that landed him in jail.

He used his parents’ divorce to justify his anger.

At 12, he’d found his father’s marriage certificate bearing another woman’s name instead of his mother’s and handed it to her.

“All hell broke loose,” he says of how his mother found out his father had a second wife. They split a year later, leaving him and his then-seven-year-old sister in their mother’s custody.

His Anger Worked Against Him

Mr Firdaus had sought stability by signing on as a regular with the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) during his national service (NS). But three years in, an accident that badly dislocated his arm reignited his anger and frustration.

“I quarrelled with the officers, I fought in camp, I absconded from work and I was even absent without official leave (AWOL).” The military police ‘ambushed’ and arrested him at his home. But he ran away from camp once more, winding up in what folks call “the hole”.

“There was only a few minutes of light a day, with only a sai tang (Hokkien for waste bin) and a bottle of water. I was locked in this cell for up to 23 hours and 55 minutes a day. That made me reflect on what I had done.”

He thought about his mother, enduring the pain of her diabetes, cancer and later, a heart attack, she visited him every week, walking about 1 km to and from the bus stop to the DB each time, sometimes meeting with only his disrespect.

“I told myself, I have to be a better son to her,” he says. By the time he was released, he’d again determined to get his life in order.

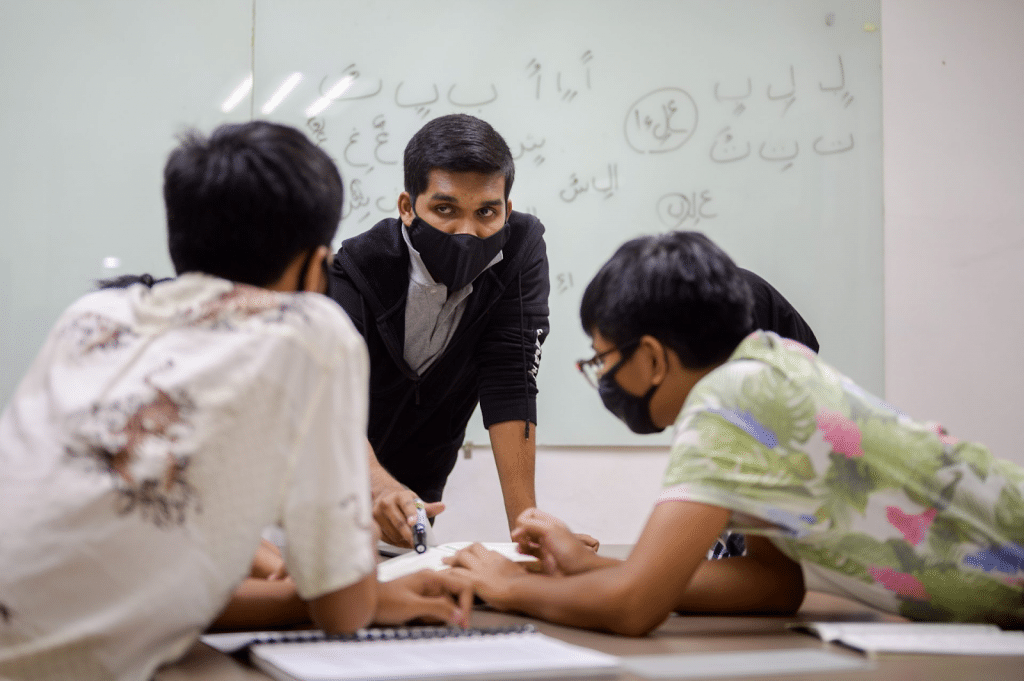

Above: Beneficiaries have the opportunity to learn language and culture at Human Hearts. Volunteer Ali teaches the difference between Jawi and Arabic script to older youths.

The Night He Nearly Lost His Wife and Three Children

Getting on track was a feat. At 25, he was married with three young children, battling the stigma of his own past.

Without proper qualifications or academic certificates, he was hardly making enough. Yet each time he sought funding for his education, “they just showed me the door every time”.

“They were not willing to support me, fearing that I would return to my old ways,” he says.

For six years he got by on a $900 wage packet as an assistant technician job at a local marine engineering company. For the following six, he worked his way up from technician to full-fledged marine engineer at a Norwegian marine company, his employers sponsoring his studies.

They also sent him on global projects across Southeast Asia, Africa and later, Saudi Arabia, earning five-figured paychecks. “I am grateful till this day to my then bosses for believing in me and giving me the opportunity to prove myself.”

He left to start his own logistics and engineering firm but when that failed, he took a contract in Saudi Arabia.

Then one night, on what was meant to be a happy return to Singapore, he almost lost his whole family.

Worn out after a long day visiting relatives during Hari Raya Puasa, he fell asleep at the wheel and ploughed the family car into a big tree.

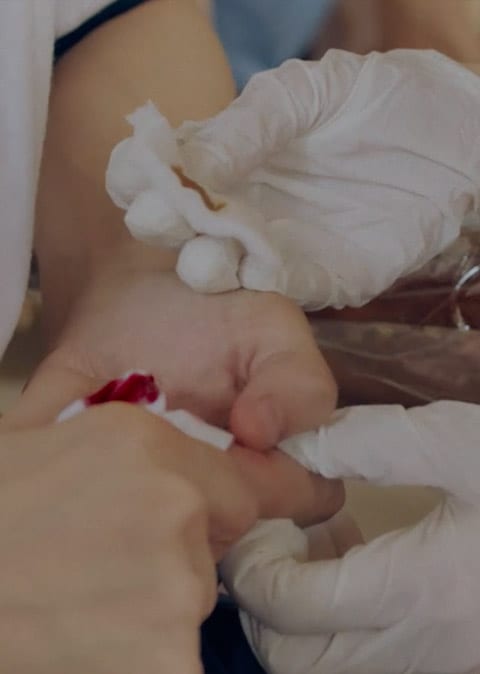

Mr Firdaus, his Filipino wife Madam Farah Dillah Abdullah, and their three children, then 12, 10 and eight, were seriously injured.

The ordeal lasted almost a year, with his family “going in and out of the National University Hospital (NUH)”.

“My wife was in a coma and was in intensive care for two weeks, and the high dependency ward for about a month. She went through five major surgeries to fix all her broken bones, and had 12 metal plates implanted in her,” he says, adding that she was known to her doctors as the bionic woman.

His children suffered multiple injuries, and daughter Aqisha is still undergoing surgery. She just had reconstruction of her leg in July and is recovering, he says.

Mr Firdaus himself sustained two fractured ribs.

The accident ravaged him mentally, physically and financially. The trauma caused flashbacks that kept him from sleep, and he worried about mounting medical bills.

“To make matters worse, I lost my job after I requested three months of unpaid leave to take care of my children,” he adds.

Only the fact that they were alive kept him going. “I had to be positive and remain strong for them. Allah answered my prayers by not taking them. I’m thankful for that and so I want to live life paying it forward.”

Despite the roller-coaster ride, he said: “It has made my family and I stronger than ever.”

Above: Volunteer interns work with children under Human Hearts’ care to build a puppet theatre for a storytelling competition.

Helping Ex-Offenders Make the Right Life Choices to Get Back on Track

At 38, Mr Firdaus found himself on a completely different path.

Funded by the Mendaki Study Award in 2018, he completed his diploma programme in counselling at Kaplan Singapore while working as a freelance marine engineer, graduating in August 2019.

With a group of like-minded reformers — ex-offenders who have made something of their lives and are now paying it forward — he founded Human Hearts, a non-profit organisation which focused on the current and ex-offender’s holistic development in social, emotional, psychological and spiritual journey towards recovery.

Integrating social, education, behaviour and cognitive intervention for long-term recovery, Mr Firdaus says, it empowers individuals through motivational and skill development.

Its aim: “To create opportunities for work and learning exposure for our beneficiaries so they have meaningful lives ahead of them even through problems and challenges.”

Self-funded and operating at a low-cost, the organisation’s affordable and, at times, free programmes for clients help them stay relevant and engaged in the community.

“These include speech and language training, language and literacy, and counselling and learning-support for offenders’ children with learning and behaviour issues in school,” he adds.

One needs to have been through the system as an offender to be able to know and understand what an ex-offender is going through.

“To an ordinary person, attending a court session is merely that. But to someone who had been an ex-offender, attending a court session usually sends chills down the spine and turns the blood cold. I guess that’s equivalent to PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder),” he says.

Who Better Than an Ex-Offender to Help Others?

To encourage its beneficiaries, Human Hearts creates a bond and trust by finding out what they want and need before helping them attain these goals.

One success story is 13-year-old Nadia, whose mother is in recovery. Nadia has dyslexia and because of that, she never really learnt to read or write, even though she attended mainstream school.

“At Human Hearts, we helped her manage her dyslexia and in just months, she learnt to read and write, albeit slowly. She recently wrote and illustrated her own book using the computer. It was published at the start of August and is now on sale on Amazon Books. She has regained her confidence and we are so proud of her,” Mr Firdaus says.

Today, Mr Firdaus has been offered to do a double major in Psychology and Criminology and is hoping to be able to receive funding from a philanthropic organisation to continue his education.

“I was so happy with the acceptance letter that I had it framed. Not in a million years did I think someone like me, who did not even graduate from secondary school, is offered the opportunity to do a double major. My late parents would have been so proud.”

Photos by: Joe Nair | Words by: Judith Tan

In partnership with What Are You Doing SG, a platform capturing the stories of people in Singapore, their challenges, collaborative nature and problem-solving spirit.